TABE Reading Practice Test 3

This is a timed quiz. You will be given 60 seconds per question. Are you ready?

In this passage a Mexican American historian describes a technique she used as part of her research. Doña Teodora offered me yet another cup of strong, black coffee. The aroma of the big, paper-thin Sonoran tortillas filled the small, linoleum-covered kitchen, and I Line knew that with the coffee I would receive a buttered tortilla 5 straight from the round, homemade comal (a flat, earthen- ware cooking pan) balanced on the gas-burning stove. For three days, from ten in the morning until early evening, I had been sitting in the same comfortable wooden chair, taking cup after cup of black coffee and consuming hot 10 tortillas. Doña Teodora was ninety years old, and although she would take occasional breaks from patting, extending, and turning over tortillas to let her cat in or out, it appeared that I was the only one exhausted at the end of the day. But once out, as I went over the notes, filed and organized the 15 tape cassettes, exhilaration would set in. The intellectual and emotional excitement I had previously experienced when a pertinent document would suddenly appear now waned in comparison to the gestures and words, the joy and anger doña Teodora offered. 20 She had not written down her thoughts; but the ideas, recollections, and images evoked by her lively oral expres- sion were jewels for anyone who wanted to know about the life of Mexicanas * in booming mining towns on both sides of the Mexico-United States border in the early twentieth 25 century. She never kept a diary. The thought of writing a memoir would have been put aside as presumptuous. But all her life doña Teodora had lived amidst the telling and retelling of family stories. Genealogies of her own family as well as complete and up-to-date information of the 30 marriages, births, and deaths of numerous families that made up her community were all well-kept memories. These chains of generations were fleshed out with recollec- tions of the many events and tribulations of these families. Oral history had proven to be a fertile field for my research 35 on the history of Mexicanas. My search had begun in libraries and archives—reposi- tories of conventional history. The available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information. These, however, as 40 important as they are, cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience that defies quantification and classification. In certain social groups this gap can be filled with diaries, memoirs, letters, or even reports from others. In the case of 45 Mexicanas in the United States, one of the many devastating consequences of defeat and conquest has been that the traditional institutions that preserve and transfer culture (the documentation of the past) have ignored these personal written sources. The letters, writings, and documents of 50 Mexican people have rarely, if ever, been included in archives, special collections, or libraries. At best, some centers have attempted to collect newspapers published by Mexicans, but the effort was started late. The historian who tries to reconstruct the past from newspapers is constantly 55 frustrated because, although titles abound, collections are scarce and often incomplete. Although many hours of previous study and preparation had taken me to doña Teodora's kitchen, I was initially unsure of my place. Was I really an insider or were the 60 experiences that had made the lives of my interviewees such that, although I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana, I was still an outsider? I realized, nonetheless, that the richness and depth of the spoken word challenges the comforting theories and models 65 of the social sciences. Mexican history challenges social- science models derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences. Our history cannot be written without new sources. These sources will determine which concepts are needed to 70 illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves. This will permit the description of events and structures to assume a culturally relevant perspective, thus emphasizing the point of view of the Mexican people. The use of theoretical constructs must 75 follow the voices of the people who live the reality, con- sciously or not. For too long the experiences of women have been studied according to male-oriented sources and constructs. These must be questioned. For the history of Mexican people, the sources primarily exist in our own 80 worlds. And it is here where we must begin. I often found that as the memory awakened, other sources would emerge. Boxes of letters, photographs, and even manuscripts and diaries would appear. Long-standing assumptions of illiteracy were shattered and had to be reexamined. I saw 85 that constant reevaluation became the rule rather than the exception. I entered women's worlds created on the margin —not only of Anglo life, but of, and outside of, the lives of their own fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, or priests, bosses, and bureaucrats. In what sense are "census reports, church records, directories" (line 38) inadequate?

The “census reports, church records and directories” (line 38) are representative of the “available sources” (line 37) that the author finds inadequate specifically because they “cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience” (lines 40-42). That is, they do not tell the human side of the story.

In this passage a Mexican American historian describes a technique she used as part of her research. Doña Teodora offered me yet another cup of strong, black coffee. The aroma of the big, paper-thin Sonoran tortillas filled the small, linoleum-covered kitchen, and I Line knew that with the coffee I would receive a buttered tortilla 5 straight from the round, homemade comal (a flat, earthen- ware cooking pan) balanced on the gas-burning stove. For three days, from ten in the morning until early evening, I had been sitting in the same comfortable wooden chair, taking cup after cup of black coffee and consuming hot 10 tortillas. Doña Teodora was ninety years old, and although she would take occasional breaks from patting, extending, and turning over tortillas to let her cat in or out, it appeared that I was the only one exhausted at the end of the day. But once out, as I went over the notes, filed and organized the 15 tape cassettes, exhilaration would set in. The intellectual and emotional excitement I had previously experienced when a pertinent document would suddenly appear now waned in comparison to the gestures and words, the joy and anger doña Teodora offered. 20 She had not written down her thoughts; but the ideas, recollections, and images evoked by her lively oral expres- sion were jewels for anyone who wanted to know about the life of Mexicanas * in booming mining towns on both sides of the Mexico-United States border in the early twentieth 25 century. She never kept a diary. The thought of writing a memoir would have been put aside as presumptuous. But all her life doña Teodora had lived amidst the telling and retelling of family stories. Genealogies of her own family as well as complete and up-to-date information of the 30 marriages, births, and deaths of numerous families that made up her community were all well-kept memories. These chains of generations were fleshed out with recollec- tions of the many events and tribulations of these families. Oral history had proven to be a fertile field for my research 35 on the history of Mexicanas. My search had begun in libraries and archives—reposi- tories of conventional history. The available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information. These, however, as 40 important as they are, cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience that defies quantification and classification. In certain social groups this gap can be filled with diaries, memoirs, letters, or even reports from others. In the case of 45 Mexicanas in the United States, one of the many devastating consequences of defeat and conquest has been that the traditional institutions that preserve and transfer culture (the documentation of the past) have ignored these personal written sources. The letters, writings, and documents of 50 Mexican people have rarely, if ever, been included in archives, special collections, or libraries. At best, some centers have attempted to collect newspapers published by Mexicans, but the effort was started late. The historian who tries to reconstruct the past from newspapers is constantly 55 frustrated because, although titles abound, collections are scarce and often incomplete. Although many hours of previous study and preparation had taken me to doña Teodora's kitchen, I was initially unsure of my place. Was I really an insider or were the 60 experiences that had made the lives of my interviewees such that, although I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana, I was still an outsider? I realized, nonetheless, that the richness and depth of the spoken word challenges the comforting theories and models 65 of the social sciences. Mexican history challenges social- science models derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences. Our history cannot be written without new sources. These sources will determine which concepts are needed to 70 illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves. This will permit the description of events and structures to assume a culturally relevant perspective, thus emphasizing the point of view of the Mexican people. The use of theoretical constructs must 75 follow the voices of the people who live the reality, con- sciously or not. For too long the experiences of women have been studied according to male-oriented sources and constructs. These must be questioned. For the history of Mexican people, the sources primarily exist in our own 80 worlds. And it is here where we must begin. I often found that as the memory awakened, other sources would emerge. Boxes of letters, photographs, and even manuscripts and diaries would appear. Long-standing assumptions of illiteracy were shattered and had to be reexamined. I saw 85 that constant reevaluation became the rule rather than the exception. I entered women's worlds created on the margin —not only of Anglo life, but of, and outside of, the lives of their own fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, or priests, bosses, and bureaucrats. Which statement most accurately presents the author's sense of the relationship between the "spoken word" (line 64) and the "theories and models of the social sciences" (lines 64-65)?

The author suggests that the spoken word can provide greater insight than the existing theories and models that are “derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences” (lines 66-67). These presently accepted theories and models are considered problematic by the author because they were developed without the insights of the Mexican people. She argues that “theoretical constructs must follow the voices of the people who live the reality” (lines 74-75).

Who Deserves Immortality? (1) By creating monuments to their brilliance, America has traditionally honored its heroes. It would be difficult to find a town in America without at least a tiny statue honoring a significant individual. However, in recent years, some of the monuments we have built have come under scrutiny. Should we demolish monuments honoring people with a contentious past? (2) Monuments honoring generals and combatants from the Confederate Army during the Civil War are currently the most contentious monuments in America. How much should America respect those who left the union in an effort to maintain their ownership of slaves? Slavery is America's greatest sin, and the South is not only to responsible for this abomination; the Confederate Army was so opposed to the idea of abolition that they were prepared to wage war. These monuments' detractors contend that we shouldn't memorialize this kind of person and that recognizing them would be a continual insult to the people of color who now enjoy freedom in our nation. (3) Supporters of these monuments contend that removing them would be an effort to erase the history of our nation. They contend that it's crucial for us to commemorate the Civil War heroes from both sides. However, organizations in favor of these monuments frequently make the completely untrue claim that slavery played a minimal role in the Civil War. (4) The controversy over Civil War statues also brings to light the 600 or so monuments and tributes to one of America's most significant and contentious historical personalities. Christopher Columbus is credited with discovering America and creating this nation, according to people who adore his sculptures. Christopher Columbus conquered America and committed genocide (whether on purpose or accidentally, according to those who oppose his memorials) in order to seize control over a new continent. Is it OK to honor a man who killed tens of thousands of innocent people? (5) At the moment, America is having identity issues. The nation is attempting to determine the best way to honor our past while ignoring its flaws. The defense of these monuments asserts that to remove them would be to attempt to forget history. However, as monuments are designed to celebrate role models, America should remove any honoring of individuals who have committed acts of hatred and violence, such as Christopher Columbus and Confederate troops. We should make sure that our history books cover these individuals because they played significant roles in American history. But only the real American heroes deserve a place on our monuments. Which of the following best sums up the article's organizational structure?

Explanation:

The answer choice (D) is accurate since the author introduces the issue at the beginning of the piece before gradually coming to the conclusion that certain monuments honoring villains should be demolished in the United States.

In this passage a Mexican American historian describes a technique she used as part of her research. Doña Teodora offered me yet another cup of strong, black coffee. The aroma of the big, paper-thin Sonoran tortillas filled the small, linoleum-covered kitchen, and I Line knew that with the coffee I would receive a buttered tortilla 5 straight from the round, homemade comal (a flat, earthen- ware cooking pan) balanced on the gas-burning stove. For three days, from ten in the morning until early evening, I had been sitting in the same comfortable wooden chair, taking cup after cup of black coffee and consuming hot 10 tortillas. Doña Teodora was ninety years old, and although she would take occasional breaks from patting, extending, and turning over tortillas to let her cat in or out, it appeared that I was the only one exhausted at the end of the day. But once out, as I went over the notes, filed and organized the 15 tape cassettes, exhilaration would set in. The intellectual and emotional excitement I had previously experienced when a pertinent document would suddenly appear now waned in comparison to the gestures and words, the joy and anger doña Teodora offered. 20 She had not written down her thoughts; but the ideas, recollections, and images evoked by her lively oral expres- sion were jewels for anyone who wanted to know about the life of Mexicanas * in booming mining towns on both sides of the Mexico-United States border in the early twentieth 25 century. She never kept a diary. The thought of writing a memoir would have been put aside as presumptuous. But all her life doña Teodora had lived amidst the telling and retelling of family stories. Genealogies of her own family as well as complete and up-to-date information of the 30 marriages, births, and deaths of numerous families that made up her community were all well-kept memories. These chains of generations were fleshed out with recollec- tions of the many events and tribulations of these families. Oral history had proven to be a fertile field for my research 35 on the history of Mexicanas. My search had begun in libraries and archives—reposi- tories of conventional history. The available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information. These, however, as 40 important as they are, cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience that defies quantification and classification. In certain social groups this gap can be filled with diaries, memoirs, letters, or even reports from others. In the case of 45 Mexicanas in the United States, one of the many devastating consequences of defeat and conquest has been that the traditional institutions that preserve and transfer culture (the documentation of the past) have ignored these personal written sources. The letters, writings, and documents of 50 Mexican people have rarely, if ever, been included in archives, special collections, or libraries. At best, some centers have attempted to collect newspapers published by Mexicans, but the effort was started late. The historian who tries to reconstruct the past from newspapers is constantly 55 frustrated because, although titles abound, collections are scarce and often incomplete. Although many hours of previous study and preparation had taken me to doña Teodora's kitchen, I was initially unsure of my place. Was I really an insider or were the 60 experiences that had made the lives of my interviewees such that, although I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana, I was still an outsider? I realized, nonetheless, that the richness and depth of the spoken word challenges the comforting theories and models 65 of the social sciences. Mexican history challenges social- science models derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences. Our history cannot be written without new sources. These sources will determine which concepts are needed to 70 illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves. This will permit the description of events and structures to assume a culturally relevant perspective, thus emphasizing the point of view of the Mexican people. The use of theoretical constructs must 75 follow the voices of the people who live the reality, con- sciously or not. For too long the experiences of women have been studied according to male-oriented sources and constructs. These must be questioned. For the history of Mexican people, the sources primarily exist in our own 80 worlds. And it is here where we must begin. I often found that as the memory awakened, other sources would emerge. Boxes of letters, photographs, and even manuscripts and diaries would appear. Long-standing assumptions of illiteracy were shattered and had to be reexamined. I saw 85 that constant reevaluation became the rule rather than the exception. I entered women's worlds created on the margin —not only of Anglo life, but of, and outside of, the lives of their own fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, or priests, bosses, and bureaucrats. The "gap" referred to in line 43 can best be described as the distance between the

The “gap” (line 43) is discussed in the context of written sources and the pictures of life they represent. The author discovered that fact-based conventional records lacked “one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience” (lines 40-42). She suggests that “diaries, memoirs, and letters” (lines 43-44), which are included in the category of “personal written sources” (lines 48-49), would present that other viewpoint. The “gap” lies between these two types of sources.

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Franklin did suggest the notion in 1784, but the United States didn't implement Daylight Saving Time until 1918—more than a century after his passing—after other European nations had already accepted the practice. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We enjoy it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Part A Which of these best describes the article's main idea?

Explanation:

The article's main idea—that we observe Daylight Saving Time because we prefer having extra sunlight throughout the summer—is only partially captured by answer choice (C). Though it might be true, answer option (B) is not the article's major point.

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Franklin did suggest the notion in 1784, but the United States didn't implement Daylight Saving Time until 1918—more than a century after his passing—after other European nations had already accepted the practice. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We enjoy it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Which of the following best describes how paragraph one fits into the article's overall structure?

Explanation:

Answer option (D) is appropriate since the author makes a point of highlighting how peculiar Daylight Savings Time is in the opening paragraph. It may be tempting to choose option (A), however the author never refers to this practice as a "problem" or makes an effort to provide a "solution."

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Though Benjamin Franklin did put out the proposal in 1784, it wasn't until 1918—more than 100 years after Franklin's passing—that America finally embraced Daylight Saving Time. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have attempted to defend the benefits of Daylight Saving Time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We like it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Part B Which of the following sentences from the article best supports the answer to Part A?

Explanation:

Answer Choice 1 is the only quote that shows that the author thinks Daylight Savings Time will continue (A). None of the other options support the answer to Part A.

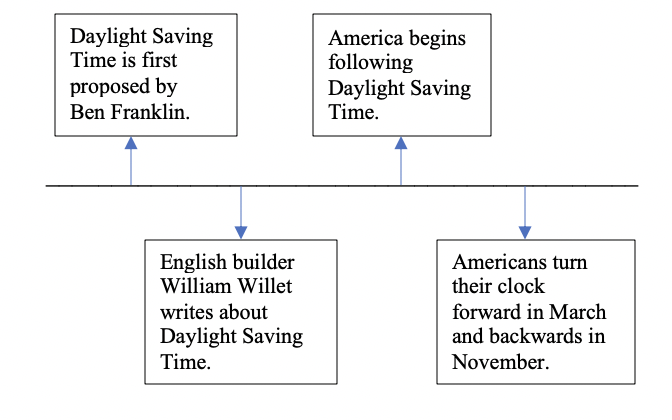

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Franklin did suggest the notion in 1784, but the United States didn't implement Daylight Saving Time until 1918—more than a century after his passing—after other European nations had already accepted the practice. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We enjoy it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Based on the article, which of the following timeframes accurately depicts the development of Daylight Saving Time?

Explanation:

The right response is (A), as it adheres to the timetable covered in Paragraph 2. Although it was Ben Franklin who first proposed the notion, it wasn't until the early 20th century that Europe followed suit. The United States followed suit in 1918, and we have now observed Daylight Saving Time for a century.

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Franklin did suggest the notion in 1784, but the United States didn't implement Daylight Saving Time until 1918—more than a century after his passing—after other European nations had already accepted the practice. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We enjoy it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Which of these summaries best captures the article?

Explanation:

The author clarifies Daylight Saving Time for readers and concludes by suggesting that it won't be changed anytime soon because people like it. Therefore, answer choice (B) is correct. Nothing in the text suggests that the author intends to put an end to it (A) or that farmers need it (C). The author doesn't advocate Daylight Saving Time as a method to memorialize Ben Franklin, despite the fact that some people may think it is (D).

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Franklin did suggest the notion in 1784, but the United States didn't implement Daylight Saving Time until 1918—more than a century after his passing—after other European nations had already accepted the practice. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We enjoy it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Read the following passage from the article. Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. What other word has the same meaning as inception in the context of this sentence?

Explanation:

Since "where anything initially originated" is the definition of inception, answer option (A) is correct. The author of the article mentions that Daylight Saving Time was first used in America one hundred years ago. Although it may be tempting, answer choice (B) does not indicate that Daylight Saving Time was changed in 1918; rather, it indicates that America started observing it.

In this passage a Mexican American historian describes a technique she used as part of her research. Doña Teodora offered me yet another cup of strong, black coffee. The aroma of the big, paper-thin Sonoran tortillas filled the small, linoleum-covered kitchen, and I Line knew that with the coffee I would receive a buttered tortilla 5 straight from the round, homemade comal (a flat, earthen- ware cooking pan) balanced on the gas-burning stove. For three days, from ten in the morning until early evening, I had been sitting in the same comfortable wooden chair, taking cup after cup of black coffee and consuming hot 10 tortillas. Doña Teodora was ninety years old, and although she would take occasional breaks from patting, extending, and turning over tortillas to let her cat in or out, it appeared that I was the only one exhausted at the end of the day. But once out, as I went over the notes, filed and organized the 15 tape cassettes, exhilaration would set in. The intellectual and emotional excitement I had previously experienced when a pertinent document would suddenly appear now waned in comparison to the gestures and words, the joy and anger doña Teodora offered. 20 She had not written down her thoughts; but the ideas, recollections, and images evoked by her lively oral expres- sion were jewels for anyone who wanted to know about the life of Mexicanas * in booming mining towns on both sides of the Mexico-United States border in the early twentieth 25 century. She never kept a diary. The thought of writing a memoir would have been put aside as presumptuous. But all her life doña Teodora had lived amidst the telling and retelling of family stories. Genealogies of her own family as well as complete and up-to-date information of the 30 marriages, births, and deaths of numerous families that made up her community were all well-kept memories. These chains of generations were fleshed out with recollec- tions of the many events and tribulations of these families. Oral history had proven to be a fertile field for my research 35 on the history of Mexicanas. My search had begun in libraries and archives—reposi- tories of conventional history. The available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information. These, however, as 40 important as they are, cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience that defies quantification and classification. In certain social groups this gap can be filled with diaries, memoirs, letters, or even reports from others. In the case of 45 Mexicanas in the United States, one of the many devastating consequences of defeat and conquest has been that the traditional institutions that preserve and transfer culture (the documentation of the past) have ignored these personal written sources. The letters, writings, and documents of 50 Mexican people have rarely, if ever, been included in archives, special collections, or libraries. At best, some centers have attempted to collect newspapers published by Mexicans, but the effort was started late. The historian who tries to reconstruct the past from newspapers is constantly 55 frustrated because, although titles abound, collections are scarce and often incomplete. Although many hours of previous study and preparation had taken me to doña Teodora's kitchen, I was initially unsure of my place. Was I really an insider or were the 60 experiences that had made the lives of my interviewees such that, although I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana, I was still an outsider? I realized, nonetheless, that the richness and depth of the spoken word challenges the comforting theories and models 65 of the social sciences. Mexican history challenges social- science models derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences. Our history cannot be written without new sources. These sources will determine which concepts are needed to 70 illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves. This will permit the description of events and structures to assume a culturally relevant perspective, thus emphasizing the point of view of the Mexican people. The use of theoretical constructs must 75 follow the voices of the people who live the reality, con- sciously or not. For too long the experiences of women have been studied according to male-oriented sources and constructs. These must be questioned. For the history of Mexican people, the sources primarily exist in our own 80 worlds. And it is here where we must begin. I often found that as the memory awakened, other sources would emerge. Boxes of letters, photographs, and even manuscripts and diaries would appear. Long-standing assumptions of illiteracy were shattered and had to be reexamined. I saw 85 that constant reevaluation became the rule rather than the exception. I entered women's worlds created on the margin —not only of Anglo life, but of, and outside of, the lives of their own fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, or priests, bosses, and bureaucrats. The author's comments in the third paragraph (lines 36-56) suggest that her research project resembles more conventional research in its

The author identifies the starting point of her research project when she writes “My search had begun in libraries and archives—repositories of conventional history” (lines 36-37). In these places, she discovered that the “available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information” (lines 37-39). These sources all share the characteristic of being written public materials.

In this passage a Mexican American historian describes a technique she used as part of her research. Doña Teodora offered me yet another cup of strong, black coffee. The aroma of the big, paper-thin Sonoran tortillas filled the small, linoleum-covered kitchen, and I Line knew that with the coffee I would receive a buttered tortilla 5 straight from the round, homemade comal (a flat, earthen- ware cooking pan) balanced on the gas-burning stove. For three days, from ten in the morning until early evening, I had been sitting in the same comfortable wooden chair, taking cup after cup of black coffee and consuming hot 10 tortillas. Doña Teodora was ninety years old, and although she would take occasional breaks from patting, extending, and turning over tortillas to let her cat in or out, it appeared that I was the only one exhausted at the end of the day. But once out, as I went over the notes, filed and organized the 15 tape cassettes, exhilaration would set in. The intellectual and emotional excitement I had previously experienced when a pertinent document would suddenly appear now waned in comparison to the gestures and words, the joy and anger doña Teodora offered. 20 She had not written down her thoughts; but the ideas, recollections, and images evoked by her lively oral expres- sion were jewels for anyone who wanted to know about the life of Mexicanas * in booming mining towns on both sides of the Mexico-United States border in the early twentieth 25 century. She never kept a diary. The thought of writing a memoir would have been put aside as presumptuous. But all her life doña Teodora had lived amidst the telling and retelling of family stories. Genealogies of her own family as well as complete and up-to-date information of the 30 marriages, births, and deaths of numerous families that made up her community were all well-kept memories. These chains of generations were fleshed out with recollec- tions of the many events and tribulations of these families. Oral history had proven to be a fertile field for my research 35 on the history of Mexicanas. My search had begun in libraries and archives—reposi- tories of conventional history. The available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information. These, however, as 40 important as they are, cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience that defies quantification and classification. In certain social groups this gap can be filled with diaries, memoirs, letters, or even reports from others. In the case of 45 Mexicanas in the United States, one of the many devastating consequences of defeat and conquest has been that the traditional institutions that preserve and transfer culture (the documentation of the past) have ignored these personal written sources. The letters, writings, and documents of 50 Mexican people have rarely, if ever, been included in archives, special collections, or libraries. At best, some centers have attempted to collect newspapers published by Mexicans, but the effort was started late. The historian who tries to reconstruct the past from newspapers is constantly 55 frustrated because, although titles abound, collections are scarce and often incomplete. Although many hours of previous study and preparation had taken me to doña Teodora's kitchen, I was initially unsure of my place. Was I really an insider or were the 60 experiences that had made the lives of my interviewees such that, although I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana, I was still an outsider? I realized, nonetheless, that the richness and depth of the spoken word challenges the comforting theories and models 65 of the social sciences. Mexican history challenges social- science models derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences. Our history cannot be written without new sources. These sources will determine which concepts are needed to 70 illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves. This will permit the description of events and structures to assume a culturally relevant perspective, thus emphasizing the point of view of the Mexican people. The use of theoretical constructs must 75 follow the voices of the people who live the reality, con- sciously or not. For too long the experiences of women have been studied according to male-oriented sources and constructs. These must be questioned. For the history of Mexican people, the sources primarily exist in our own 80 worlds. And it is here where we must begin. I often found that as the memory awakened, other sources would emerge. Boxes of letters, photographs, and even manuscripts and diaries would appear. Long-standing assumptions of illiteracy were shattered and had to be reexamined. I saw 85 that constant reevaluation became the rule rather than the exception. I entered women's worlds created on the margin —not only of Anglo life, but of, and outside of, the lives of their own fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, or priests, bosses, and bureaucrats. The author indicates that the "concepts" mentioned in lines 69-70 originate in

Lines 69-70 suggest that the “concepts” will originate in the “new sources” (line 68), which, the passage implies, are the oral histories and personal written sources of ordinary people. These new sources of information “will determine which concepts are needed to illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves” (lines 69-71).

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Franklin did suggest the notion in 1784, but the United States didn't implement Daylight Saving Time until 1918—more than a century after his passing—after other European nations had already accepted the practice. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We enjoy it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Why may it be incorrect to assert that Daylight Saving Time was invented by Ben Franklin?

Explanation:

The author explicitly states that although Ben Franklin may have been the first to advocate the practice, America's use of Daylight Saving Time did not derive from Franklin's proposal, making answer choice (B) valid. The article directly refutes the other response options.

In this passage a Mexican American historian describes a technique she used as part of her research. Doña Teodora offered me yet another cup of strong, black coffee. The aroma of the big, paper-thin Sonoran tortillas filled the small, linoleum-covered kitchen, and I Line knew that with the coffee I would receive a buttered tortilla 5 straight from the round, homemade comal (a flat, earthen- ware cooking pan) balanced on the gas-burning stove. For three days, from ten in the morning until early evening, I had been sitting in the same comfortable wooden chair, taking cup after cup of black coffee and consuming hot 10 tortillas. Doña Teodora was ninety years old, and although she would take occasional breaks from patting, extending, and turning over tortillas to let her cat in or out, it appeared that I was the only one exhausted at the end of the day. But once out, as I went over the notes, filed and organized the 15 tape cassettes, exhilaration would set in. The intellectual and emotional excitement I had previously experienced when a pertinent document would suddenly appear now waned in comparison to the gestures and words, the joy and anger doña Teodora offered. 20 She had not written down her thoughts; but the ideas, recollections, and images evoked by her lively oral expres- sion were jewels for anyone who wanted to know about the life of Mexicanas * in booming mining towns on both sides of the Mexico-United States border in the early twentieth 25 century. She never kept a diary. The thought of writing a memoir would have been put aside as presumptuous. But all her life doña Teodora had lived amidst the telling and retelling of family stories. Genealogies of her own family as well as complete and up-to-date information of the 30 marriages, births, and deaths of numerous families that made up her community were all well-kept memories. These chains of generations were fleshed out with recollec- tions of the many events and tribulations of these families. Oral history had proven to be a fertile field for my research 35 on the history of Mexicanas. My search had begun in libraries and archives—reposi- tories of conventional history. The available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information. These, however, as 40 important as they are, cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience that defies quantification and classification. In certain social groups this gap can be filled with diaries, memoirs, letters, or even reports from others. In the case of 45 Mexicanas in the United States, one of the many devastating consequences of defeat and conquest has been that the traditional institutions that preserve and transfer culture (the documentation of the past) have ignored these personal written sources. The letters, writings, and documents of 50 Mexican people have rarely, if ever, been included in archives, special collections, or libraries. At best, some centers have attempted to collect newspapers published by Mexicans, but the effort was started late. The historian who tries to reconstruct the past from newspapers is constantly 55 frustrated because, although titles abound, collections are scarce and often incomplete. Although many hours of previous study and preparation had taken me to doña Teodora's kitchen, I was initially unsure of my place. Was I really an insider or were the 60 experiences that had made the lives of my interviewees such that, although I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana, I was still an outsider? I realized, nonetheless, that the richness and depth of the spoken word challenges the comforting theories and models 65 of the social sciences. Mexican history challenges social- science models derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences. Our history cannot be written without new sources. These sources will determine which concepts are needed to 70 illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves. This will permit the description of events and structures to assume a culturally relevant perspective, thus emphasizing the point of view of the Mexican people. The use of theoretical constructs must 75 follow the voices of the people who live the reality, con- sciously or not. For too long the experiences of women have been studied according to male-oriented sources and constructs. These must be questioned. For the history of Mexican people, the sources primarily exist in our own 80 worlds. And it is here where we must begin. I often found that as the memory awakened, other sources would emerge. Boxes of letters, photographs, and even manuscripts and diaries would appear. Long-standing assumptions of illiteracy were shattered and had to be reexamined. I saw 85 that constant reevaluation became the rule rather than the exception. I entered women's worlds created on the margin —not only of Anglo life, but of, and outside of, the lives of their own fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, or priests, bosses, and bureaucrats. What is the effect of the question in lines 59-62?

The author acknowledges that she is connected to doña Teodora and other Mexicana interviewees through their shared ethnicity and language. She writes, "I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana" (line 61). Yet the author wonders if she was "still an outsider" (line 62). The fact that she raises this question suggests that sharing these common bonds might not be enough to make her an insider.

In this passage a Mexican American historian describes a technique she used as part of her research. Doña Teodora offered me yet another cup of strong, black coffee. The aroma of the big, paper-thin Sonoran tortillas filled the small, linoleum-covered kitchen, and I Line knew that with the coffee I would receive a buttered tortilla 5 straight from the round, homemade comal (a flat, earthen- ware cooking pan) balanced on the gas-burning stove. For three days, from ten in the morning until early evening, I had been sitting in the same comfortable wooden chair, taking cup after cup of black coffee and consuming hot 10 tortillas. Doña Teodora was ninety years old, and although she would take occasional breaks from patting, extending, and turning over tortillas to let her cat in or out, it appeared that I was the only one exhausted at the end of the day. But once out, as I went over the notes, filed and organized the 15 tape cassettes, exhilaration would set in. The intellectual and emotional excitement I had previously experienced when a pertinent document would suddenly appear now waned in comparison to the gestures and words, the joy and anger doña Teodora offered. 20 She had not written down her thoughts; but the ideas, recollections, and images evoked by her lively oral expres- sion were jewels for anyone who wanted to know about the life of Mexicanas * in booming mining towns on both sides of the Mexico-United States border in the early twentieth 25 century. She never kept a diary. The thought of writing a memoir would have been put aside as presumptuous. But all her life doña Teodora had lived amidst the telling and retelling of family stories. Genealogies of her own family as well as complete and up-to-date information of the 30 marriages, births, and deaths of numerous families that made up her community were all well-kept memories. These chains of generations were fleshed out with recollec- tions of the many events and tribulations of these families. Oral history had proven to be a fertile field for my research 35 on the history of Mexicanas. My search had begun in libraries and archives—reposi- tories of conventional history. The available sources were to be found in census reports, church records, directories, and other such statistical information. These, however, as 40 important as they are, cannot provide one of the essential dimensions of history, the full narrative of the human experience that defies quantification and classification. In certain social groups this gap can be filled with diaries, memoirs, letters, or even reports from others. In the case of 45 Mexicanas in the United States, one of the many devastating consequences of defeat and conquest has been that the traditional institutions that preserve and transfer culture (the documentation of the past) have ignored these personal written sources. The letters, writings, and documents of 50 Mexican people have rarely, if ever, been included in archives, special collections, or libraries. At best, some centers have attempted to collect newspapers published by Mexicans, but the effort was started late. The historian who tries to reconstruct the past from newspapers is constantly 55 frustrated because, although titles abound, collections are scarce and often incomplete. Although many hours of previous study and preparation had taken me to doña Teodora's kitchen, I was initially unsure of my place. Was I really an insider or were the 60 experiences that had made the lives of my interviewees such that, although I could speak Spanish and am Mexicana, I was still an outsider? I realized, nonetheless, that the richness and depth of the spoken word challenges the comforting theories and models 65 of the social sciences. Mexican history challenges social- science models derived solely from victorious imperialistic experiences. Our history cannot be written without new sources. These sources will determine which concepts are needed to 70 illuminate and interpret the past, and these concepts will emerge from the people themselves. This will permit the description of events and structures to assume a culturally relevant perspective, thus emphasizing the point of view of the Mexican people. The use of theoretical constructs must 75 follow the voices of the people who live the reality, con- sciously or not. For too long the experiences of women have been studied according to male-oriented sources and constructs. These must be questioned. For the history of Mexican people, the sources primarily exist in our own 80 worlds. And it is here where we must begin. I often found that as the memory awakened, other sources would emerge. Boxes of letters, photographs, and even manuscripts and diaries would appear. Long-standing assumptions of illiteracy were shattered and had to be reexamined. I saw 85 that constant reevaluation became the rule rather than the exception. I entered women's worlds created on the margin —not only of Anglo life, but of, and outside of, the lives of their own fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, or priests, bosses, and bureaucrats. In line 59, "place" most nearly means

A "role" is the position or the expected social behavior of an individual. When the author writes "I was initially unsure of my place" (lines 58-59), she is expressing uncertainty about how she should think of herself and about how she is perceived by doña Teodora and other Mexicana interviewees. In this context, "place" refers to her social "role." This is made clear in the subsequent text, when she wonders if, despite speaking Spanish and being Mexicana, she is an "insider" (line 59) or an "outsider" (line 62).

What Are We Saving Through Daylight Saving Time? (1) Daylight Saving Time is observed by western nations including the United States of America and the European Union every year. Although many nations observe Daylight Saving Time in different ways, they all usually adhere to the same principle. Everyone changes their clocks throughout the summer so that there is an hour more of sunlight in the evening than there would have been in the morning. Even more bizarre than this practice is the fact that most individuals don't know why Daylight Saving Time exists. People advance their clocks by one hour each March, then sometimes for no reason at all, turn them back one hour in November. (2) The majority of people only know that Benjamin Franklin first advocated Daylight Saving Time as a concept. Franklin did suggest the notion in 1784, but the United States didn't implement Daylight Saving Time until 1918—more than a century after his passing—after other European nations had already accepted the practice. Franklin's notion was well received in Europe, but no one gave it much thought until an English builder named William Willet put it up in a pamphlet in 1907. Another fact regarding Daylight Saving Time that many appear to "know" is that it was instituted to benefit farmers. Nobody appears to be aware of how that precisely works. The real explanation behind Daylight Saving Time is considerably more straightforward and innocent than that. (3) People would have more time in the evening to be outside in the sunlight because Daylight Saving Time was implemented. Why squander that lovely sunlight in the morning hours while everyone is asleep? Experts have argued for the benefits of daylight saving time ever since it was implemented in America 100 years ago. Numerous experts claim that it lowers the nation's energy bills. This is accurate, although the energy we conserve at this time is only a tiny fraction (perhaps 1%). Others contend that having more daylight in the evening keeps us safer and lowers our risk of suffering injuries in accidents. However, studies have revealed that our internal clocks do not change smoothly, which causes an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and traffic accidents every March. Why then do we continue to do it each year? (4) Once more, the response to this query is a straightforward and charming one: We enjoy it. The initial purpose of daylight saving time, which is still observed today, was to offer people an extra hour of daylight in the evening. Daylight Saving Time won't end as long as people love having that extra hour in the evening. Which of the following best sums up the article's organizational structure?

Explanation:

The author presents Daylight Savings Time at the beginning of the essay, delves into its history, and comes to a conclusion about it at the end. Therefore, answer choice (C) is accurate. The author does detail the chronological background of the practice, which makes answer option (D) alluring. However, this is only a small portion of the essay and does not accurately represent its general organization.